The Edge of Silence

It is nearly silent when I reach a false summit on the ridge, and my two companions behind me are invisible in the blowing mist. Noise travels no farther than my sight, a few yards, and I sit on a trailside rock near a small overlook to wait.

An hour ago we were lunching on cheese and wine at Refuge Robert Blanc, a French mountain hut perched at 9,000 feet, and are a few miles from our night’s stop at Refuge du Plan de la Lai. Now I stare down into the clouds from my seat. Soon they began to break, and in a moment open to reveal the roller coaster of trail and rock from which we’ve just come.

Then I glance to my right, and realize the rock I'm sitting on is actually the top of a 1,000-plus-foot cliff. To the right of the 12-inch-wide trail, the ridge drops off as well, into a 50-degree slope that looks no friendlier with its covering of grass. It looks more like an exit for a BASE jump than a hiking or biking trail, and I decide this is where I’ll start walking my bike—it seems I forgot my parachute at home. Oh, the joys of being afraid of heights in the heart of the French Alps.

Photographer Grant Gunderson and our quasi-guide Sebastien Nestolat are now visible a short distance below. We are here because of Gunderson’s efforts—we’re longtime travel partners, and so when he called me for a trip traveling between alpine huts in some of Europe’s most famous mountains I was instantly game. Both passionate skiers, we were well-versed in the glory of the French Alps and its storied system of huts. I had never expected to explore them via bikes.

Just as I pull my heart from my throat and begin to dismount, I see a French couple approaching. Probably in their 70s, they hike by with a quick “bonjour!” and without a glance at the precipitous drop that has me so gripped. “Hilarious,” I think, laughing at myself, “I’ve just been passed by a pair of grandparents.”

I don’t get back on my bike though. Pushing is just fine with me.

Our trip started a few days earlier, at the small mountain town of Bourg-Saint-Maurice, France. Bourg-Saint-Maurice is a two-hour shuttle from Switzerland’s Geneva airport, and while the 7,800-person town may not sound familiar to bikers, to any skier the surrounding resorts will: Les Arcs, Les Rosieres and Tignes, the host resort of the European Winter X Games.

The hut system we planned to explore is also well-known in the winter community, a loop that circumnavigates part of Mont Blanc and that a number of our friends have completed on skis. During the summer, the huts—maintained by the French Alpine Club—are mostly used by hikers, but we’d heard of people biking sections of the loop. We thought we could link it all together into a three-day trip—assuming it was all bikeable.

Thirty minutes later we reached the top of the Col du Petit Saint Bernard, a nearly 7,200-foot pass on the Italian/French border. There we met Nestolat. Sebastien’s main gig is running a local advertising agency, but having grown up in the area and being a passionate biker, he knows the mountains better than anyone.

As we walked from the parking lot into the nearby cow pastures, Sebastien gave us a brief history of the pass—relatively brief, as Saint Bernard has a lot to talk about. It was used by the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca, on his way to attack Rome (although his famous elephants were likely absent), and during World War II was one of France’s major holding points against the Germans. It didn’t stop them, but concrete bunkers and tank traps still riddle the ridgeline. Its biking history is road-centric; it’s seen four Tour de France stages, including in 2009 when Lance Armstrong chased down Alberto Contador and Frank Schleck.

But we weren’t there for the roads. We were there for the black ribbons cutting along the lush hills, a lacework of dirt that disappeared into one of the nearby valleys.

With Sebastien’s historical preview complete, we geared up and began the journey, rolling through cow pastures and green hills before dropping to the small Italian town of La Thuile (population 800). The street-side cafes buzzed with tourists and motorbikes, and cars flew through town on the way back and forth from the pass. We didn’t pause—we’d been warned we had a stiff climb ahead.

The trail snaked past the centuries-old stone houses of Cretez Jean and Orgeres, and with every pedal stroke we climbed further into silence and toward total exhaustion. Soon even the tiny villages dipped out of sight. The sounds of La Thuile were completely replaced by heavy breathing in the thin mountain air and the occasional ring of a cowbell.

Some 3,500 feet later we arrived at Mont Fortin, a peak located on the backside of Courmayeur Ski Resort. The Mont Blanc massif once again came into view, dominating the landscape and the valley below. In France there seems to be towns every few miles, and even in the mountains the bustle of humanity is ever-present. It makes sense, as there are 116 people per square kilometer of the country. In my home country of Canada, there are four people per square kilometer—quite the contrast.

"The edge of the trail could have been a 1,000-foot drop, but at that moment dodging cow pies and rocks was more important. ”

But when we reached the summit of Mont Fortin, we saw nothing around us but mountains. No towns, no people, no noise, just the crisp autumn breeze and a ribbon of single track that was as old as the houses of Cretez and Orgeres.

We still had 10 miles and 2,000 feet of climbing ahead, and so we began the ascent toward our accommodations for the evening: Les Mottets, a historical stone refuge located in the Valley of Glaciers. Evening was fast approaching, and by the time we finished our climb, a dense fog moved in, turning the dusk light into near darkness. Our vision was limited to a few feet, and for the next 30 minutes we focused exclusively on what was in front of us. The edge of the trail could have been a 1,000-foot drop, but at that moment dodging cow pies and rocks was more important.

The hut finally came into view at 9 p.m. In the 23 miles we had covered during the day, we had crossed from France into Italy and back into France. We had also climbed more than 5,500 feet and were exhausted.

Cold from the brisk autumn temps and beat from the day, we dragged ourselves up the stairs and into the refuge’s dining hall. Hot air and the cheers of 70 fellow hut-mates rushed out of the open door, hikers from all over the world welcoming the “crazy mountain bikers” for the night. People of all ages and nations filled the dining room with buzz and excitement, recounting their day on the trail and plans for their next.

We joined the mishmash of conversation, and Gunderson talked about the ride with a group made up of Englishmen, Japanese and a couple from Scotland. Meanwhile Sebastien chatted away with the hut-keeper in French. I contented myself with sitting back to admire the smorgasbord of humans, people separated by oceans, languages and cultures but united by their shared love of being in the mountains.

The fog and failing light the previous evening had kept our eyes on the trail; the blue skies the next morning immediately drew them to the giant glaciers hanging above the refuge, massive chunks of ice that validated the valley’s title. The sound of perpetual cowbells filled the air, and aside from our accommodations and our bovine neighbors it could have been the Alps of 500 years before. It felt like waking up in a postcard.

The day’s ride took us through the Beaufortain region, which is world famous for the production of Beaufort cheese. Officially, Beaufort comes only from the French Alps and takes as long as five years before it’s ready to eat. We stopped at a local famer’s house to buy some straight from the source. Few things are as authentic Alps as fresh trailside cheese followed by parting words you don’t understand.

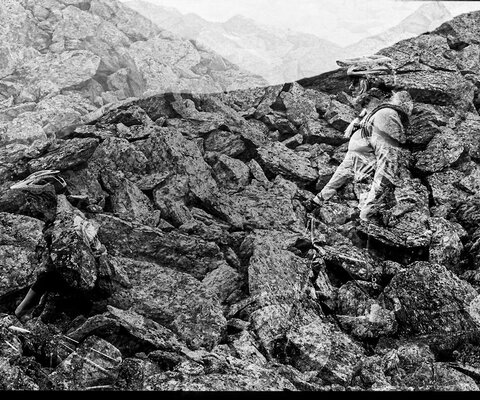

The trail morphed into a double-track road climbing halfway up the Tete Sud des Fours, at 8,500 feet one of the highest passes of the trip—and one of the most brutal climbs, as the double track soon turned back to incredibly steep single track. We found ourselves pushing our bikes up the last 700 feet of rocky trail, far different from the rolling green hills in the valley below. Upon reaching the summit, however, the view was worth the effort: Mont Blanc towered behind us, and the Valley of Glaciers looked just as picturesque from 3,000 feet above as it did while touring the farmer’s cheese factory. It was the Alps I had envisioned when I stepped off the plane in Geneva.

Our next stop was Refuge Robert Blanc, an iconic hut perched in the middle of a steep rock field. Despite the daunting location, the surrounding trails more resemble those in Fruita, CO than Utah super tech: fast, buff single track that virtually anyone could enjoy. Managed by the French Alpine Club, Robert Blanc is part of both the winter and summer versions of the Tour de Mont Blanc. It’s also a great place for midday wine and espresso.

We still had a short five miles to our final stop of the day, Refuge du Plan de la Lai, but a significant climb stood between us and the hut. It was also supposed to be one of the more impressive sections of the trip, both sides of the trail lined with huge, precarious relief. But as we started up the ridge, another thick bank of clouds rolled in, obscuring everything.

It wasn’t until an hour later that the skies cleared, revealing the length of the ridgeline in all its glory—and that I was passed by the two 70 year olds while walking my bike. Shortly after Gunderson and Sebastien reach my perch on the false summit, and after taking in the scenery we continue toward the top of the climb, following the elderly couple. I may have felt chagrined when they first passed. When both Gunderson and Sebastien decide to dismount as well, I don’t feel nearly as bad.

The descent to Refuge du Plan de la Lai is as stunning as yesterday’s was dark, the sunset gleaming as we navigate the ridge toward the hut. Unlike Les Mottets, the inhabitants here are all French, three hiker couples just finishing their dinner. They’re surprised to see we’re on bikes, and in broken French they ask us where we’re coming from. I manage a quick conversation explaining our arrival via “VTT,” the French term for mountain bike.

Soon a few bottles of Génépi—a traditional liqueur related to absinthe—comes out, and any differences between our modes of transportation disappear in the laughter filling the room. Like the mountains that have brought us here, we’re all united by pizza, Beaufort and beer.

The next morning we awake to a crackling fire and the hut-keeper prepping food for the next group of hikers coming through. Conversations in Swiss, French and German accompany our baguette and marmalade breakfast, a fittingly international start to our last day.

The plan is to ride a loop we’ve heard is one of the most impressive trails in the region, a route climbing 4,000 feet in 15 miles. We know it is going to be a big day, but we figure since it is our last we might as well go for it. A half-hour later we pedal away from the hut, heading west toward Roseland Lake and some Hollywood fame—the dam at the head of the lake appears in the opening scene of the movie The Italian Job.

The trail weaves through farmers’ fields and stereotypical cottages, then up toward the summit of Roche Parstire, a nearly 7,000-foot summit and the start of the trip’s final descent. The sunset casts a burning alpenglow against Mont Blanc, off to the northeast. It’s only been three days, but it seems I first laid eyes on its rocky bulk eons before.

Our van is parked a few thousand feet below, and the noise and chaos of a busy Friday night awaits us in town. But at the moment we’re surrounded by mountains and a silence as deep as anywhere, broken only by the sound of cowbells ringing in the twilight.