Born From Junk Trailblazers

Words by Mike Horn

"Born From Junk" part one traces the outlaw roots of mountain biking back to its raw beginnings in Crested Butte, where a crew of unlikely pioneers in pursuit of wild times in the mountains blossomed into a global phenomenon.

Part two of Born From Junk documents the rise of mountain biking as it came into its own as a full-blown sport. In less than a decade, Colorado's scene went from cruising around on klunkers, to scratching in clandestine singletrack, to riding dedicated mountain bikes on expanding networks of sanctioned trails. The sport quickly grew to attract large crowds at races in hotspots such as Gunnison and Crested Butte, eventually debuting as an Olympic sport at the 1996 Summer Games in Atlanta, Georgia.

It was the kind of town that could buck you off like an unbroken horse. The kind of Wild West that made false fronts out of more civilized towns.

The streets were unpaved. Coal smoke turned the air murky and thick during the winter months. Hitching posts lined Elk Avenue. There was little work to be had. But with that deficit came freedom and the opportunity to live in the moment. And what better place to have time on your side—and to ride a bike.

But there was more to Crested Butte in the 1970s than just that. Out of dirt and necessity came a new way to have fun in the mountains. Around 1974, a small group of rowdy locals started modifying their bikes into what became known as “klunkers”—junkyard-sourced bikes cobbled together with a mix of dirt bike, BMX and salvaged bicycle parts. These early riders thought nothing of their high-speed descents of the area’s mining roads and mountain passes. They rode and raced and partied like there was no tomorrow. There was no ambition, no plan.

And yet, this crew of friends and unlikely pioneers established some of the deepest roots in mountain biking. You won’t find their names on the current Mountain Bike Hall of Fame roster, but these were no one-ride wonders. They were right there, in the moment when something new was born. They were one of the sparks that ignited modern mountain biking. And culturally, they set a bar for having fun that the rest of us can only aspire to.

Like the Buffalo Soldiers in the 1890s and others before and after them, Crested Butte locals began riding and modifying bicycles out of necessity. In the 1970s, when the streets weren’t covered in snow, they were riddled with potholes. The kind of potholes that could make a VW Bug disappear. So, it was easier (and safer) to navigate town by bike. Plus, riding was fun. All types of characters from all points on the compass filtered into and passed through Crested Butte and the Gunnison Valley during the late 1960s and into the 1970s. Some ran from the law, the Vietnam War or ghosts from the past. Others came for the ski area and the college in Gunnison, or all of the above. They came to the end of the road for isolation, exploration and awe-inspiring verdant valleys rimmed by hulking spreads and spikes of granite that climb well above 12,000 feet. For all, this remote outpost in the West Elk Mountains provided a fresh start full of possibility. The newcomers found a community made up largely of miners and ranchers who had called Crested Butte and the Gunnison Valley home for more than 100 years. “The old timers in this town were mostly retired,” said Jim “Long Beach” Thomas, who arrived in the valley from California in 1968. “A lot of them were of Slavic descent and had worked their asses off, but there was no economy. The ski area started in ’61, and it was just getting rolling by ’68 when I got here, so these people were living pretty much off the land still, and then a bunch of hippies came to town.” Hippies and bicycles go together like tofu and broccoli, and the newcomers increasingly took to bikes to get around town. It was just a simple and inexpensive means of transportation—until a few locals started adding speed, competition and beer into the equation. “What if we haul these bikes up a mountain pass and ride them back down?” they pondered, likely over a cold one. That’s when biking transformed from a mode of transportation into a rowdy form of recreation.

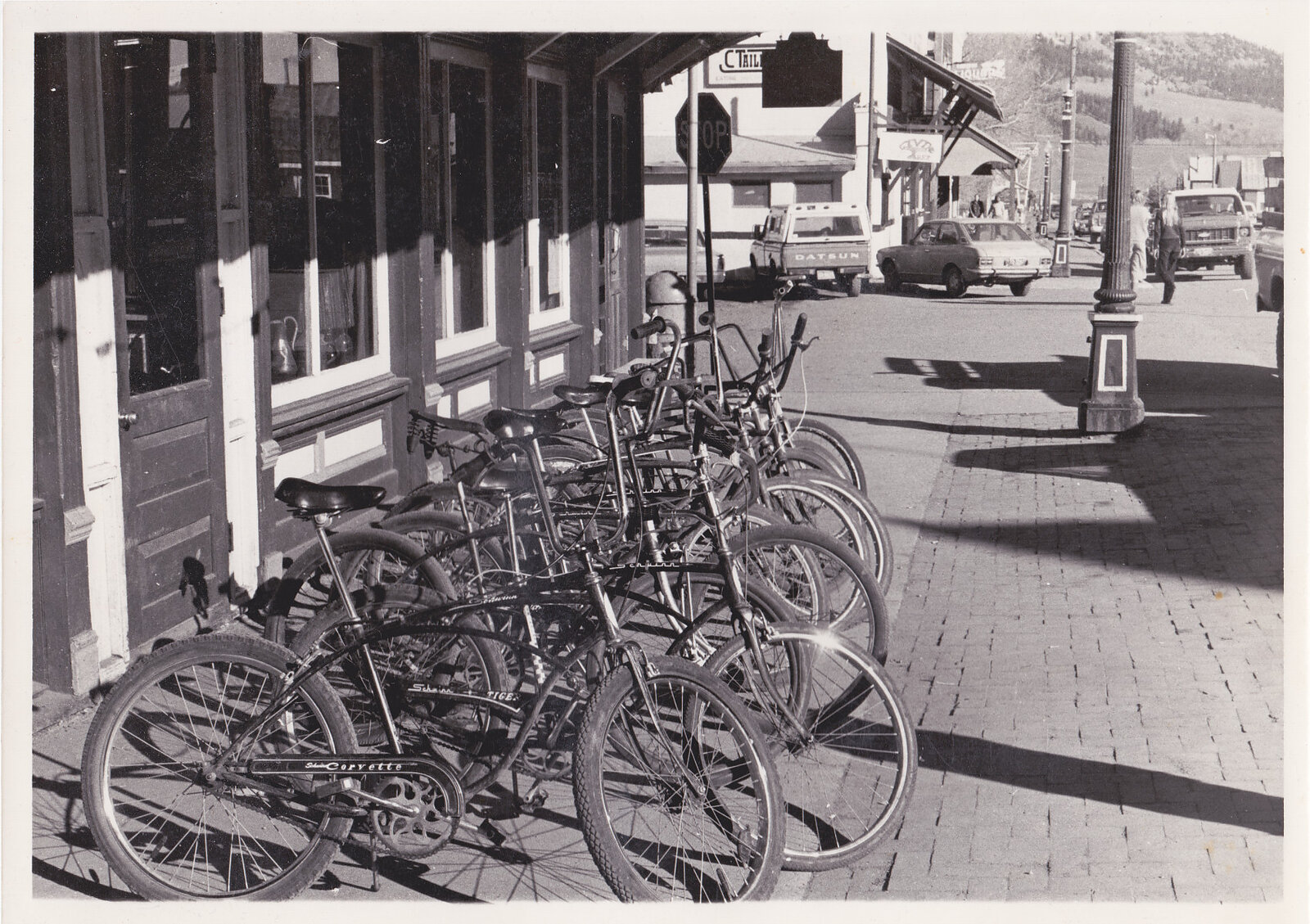

Crested Butte’s early bike scene was loose and disorganized, if there was even a scene at all. In the early 1970s, Al Maunz, arguably one of the world’s first mountain bike mechanics, started building klunkers out of junkyard-sourced frames, dirt bike and BMX parts. He and his buddy Steve Baker would drive to junkyards in Denver and around the state and fill up a pickup with castaway bikes. They’d bring them back to town, salvage the best frames—preferably pre-WWII Schwinns as intact as possible—and scavenge the rest for parts.

“Nobody got the big idea until Albert and Baker started building them,” said Crested Butte’s Bob Starr, one of the early riders. “He started doing the Denver junkyard thing, and then everybody wanted one.”

“They would fix them up in the shop, and for 15 bucks you had yourself a klunker,” Thomas added. “We’d go up and do downhill runs mainly because we didn’t have gears. Gears came later and the trail system came later. We were riding the dirt roads with jean jackets and jeans, boots and leather gloves. No helmet. Ball cap. That was your biking outfit, your Lycra back then.”

Everybody wanted in, and Baker and Maunz began taking orders. Prices eventually went up to $50 or $100 because people were looking for specific bikes. And Maunz’s franken-bike klunkers had a style all their own. No two were the same. He’d replace the high-rise handlebars with more dirt-riding-friendly bars sourced from BMX bikes. Because the coaster brake would overheat and seize up when ridden downhill, he replaced the coaster with a dirt-bike handbrake. These klunkers could weigh 60-plus pounds and were geared for descending—riding uphill really wasn’t an option.

Word soon got around that Maunz and the rest of the “Grubstake Gang” (a nickname inspired by their favorite bar in town) were bombing down mining roads and mountain passes on klunkers. People were intrigued.

“They’d see us on them, and we’d park them in front of the bars, back them in like motorcycles, line them up,” said Maunz. “People would see them and say, ‘Man, we want one of those.’ So that’s how we started making a bunch of them.”

Maunz continued, “The chosen ones had the bikes. We made them for our friends.”

Many of the newcomers showed up in town with big ideas and empty bank accounts. But they had a lot of free time to tinker with new ideas and explore new places.

“There wasn’t a lot of work,” said Starr. “We weren’t really burdened with responsibilities and stuff. You know, everybody was single and broke, looking for shit to do that didn’t cost anything.”

In this case, that meant loading a bunch of klunkers into the back of a pickup truck and driving into the mountains in search of mining roads that could double as downhill track. Riding … racing … drinking … riding some more. It was a party on two wheels, but there was always a competitive edge. Nobody wanted to come in last — that meant you had to eat a slice of humble pie and buy the first round of beers at the Grubstake back in town.

“We were trying to get back first,” said Thomas. “We were racing. We were all competitive. If you’re going to be out there you want to be the first guy in the bar. Just bragging rights. But there was a technique involved. Laying them down and bringing them back up … and you had to know how to go down because you’re on gravel. You’re gonna go down … a lot.”

In 1976, the Grubstake Gang and friends hatched the idea for Crested Butte’s first “organized” bike event, the Pearl Pass Tour. As the story goes (and accounts vary), in the summer of 1976 a group of dirt bikers rode over to Crested Butte from Aspen to drink in the local bars and cause some good-natured trouble. This allegedly ruffled the feathers of the Grubstake Gang, who then decided to ride their klunkers over to Aspen via Pearl Pass, park their bikes at the historic Jerome Bar and Hotel, get drunk and raise hell.

With a summit of 12,705 feet, Pearl Pass is a dramatic rite and route of passage between Crested Butte and Aspen. The two towns lie only 25 miles apart as the crow flies, but culturally there has always been an air of competition over which is the more core mountain town community. In many ways, that ship has sailed, but in the 1970s Crested Buttians didn’t care much for their wealthier and more upscale brethren on the other side of the West Elk Mountains.

Crested Butte local Rick Verplank is credited by Starr and others with making the 1976 Pearl Pass Tour happen. “We had a pickup truck full of booze and stuff,” said Starr. “It had this old bathtub in the back, among other things. This guy Richard Ullery rode over the pass in the bathtub. He had a broken leg or something. We scheduled it and did it, but we didn’t have any committee meetings or anything.”

As reported in the 1976 Crested Butte Pilot, 15 klunker riders started and all but seven dropped out before reaching basecamp three miles from Pearl Pass summit. The seven included Bob Starr, Rick Verplank, Walter Keith, Jim “Long Beach” Thomas, Patty Ann Gifford, Patty Christie and Duane Reading. Verplank and Starr were reportedly the only two who “officially” made it over the pass.

“The first tour [we were] bandits, outlaw bandits,” said Maunz. “We were there partying, you know? Anywhere we went we seemed to create trouble. I think the alcohol had a lot to do with it. It wasn’t about biking. We were drinking and partying and celebrating our ride over Pearl. We weren’t talking about mountain biking at all.”

The following winter (1976-77) was bleak. Locals called it the “Winter of Un” and/or the “Year of None” due to the lack of snowfall.

“So right in the middle of the winter we had a bike fest and set up a trail through town,” recalled Thomas. “Everybody was racing. We had a jumping contest right in front of the Grubstake. The funniest guys were the ones that tried to do it one-handed with a beer in their hand, high-rise handlebars and all. I think that was one of the things that really kicked it off—that one festival in the middle of the winter, unique, mountain biking.”

No matter the season or reason, locals’ love affair with bicycles was in full bloom. Bikes became increasingly entrenched in daily life, whether riding them to work, racing them through town in the middle of winter, or sending it down a mountain pass with reckless abandon.

The Pearl Pass Tour didn’t happen in 1977. Some of the local riders were hotshots and out of town that September fighting fires. If not for a story published in the spring 1978 edition of a magazine titled Coevolution Quarterly, the Pearl Pass Tour might have been nothing more than a one-off ride to mess with the people of Aspen. And Crested Butte’s role in the evolution of biking could have taken a different path. But through that story, and a writer named Richard Nielsen, tales of outlaws and klunkers found their way to Marin County, California, where Joe Breeze and others were pioneering their own style of dirt riding on the fire roads of Mount Tamalpais.

“We met up in Fairfax [with the writer, Nielsen] in December or November of 1977 for that story,” recalled Breeze, curator of the Marin Bicycle Museum and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame. “He told us about these guys out in Crested Butte doing the same darn thing.”

Breeze, Charlie Kelly, Wende Cragg and friends from California found the story of these riders in the Rockies compelling enough to plan a trip to Crested Butte for the second Pearl Pass Tour in September 1978. They managed to contact someone at the Grubstake to let the local riders know they’d be coming out for the tour. Then, the rendezvous was largely forgotten until the California crew showed up in town, ready to ride, in September 1978. After some hemming and hawing and last-minute planning, the second tour came together and 13 riders made it to the summit that year.

“The second [Pearl Pass Tour] was totally opposite,” said Maunz. “Serious people that were riding bikes. People that didn’t drink and ride their bikes. The serious riders with the serious mountain bikes.”

Some of the riders from California had a road racing pedigree and showed up riding purpose-built, first-generation mountain bikes built by Joe Breeze and called “Breezers.” While Crested Butte’s klunkers were built from salvaged bike frames and pirated BMX and dirt bike parts, Breeze’s bikes more closely resembled the modern mountain bikes of today. It represented an aha moment for the Colorado riders, who saw for the first time that riding bikes in the mountains might become something more than shuttle rides and klunkers that only went downhill. The floodgates of innovation had opened.

In the age before the internet and social media, the exchange of ideas and technology happened at a much slower, albeit more intimate, pace. The first generation of Crested Butte riders had no idea that Breeze and friends in California were racing down dirt roads and developing purpose-built mountain bikes. Chances are, they wouldn’t have cared. It wouldn’t have stopped them from banding together over a shared passion for bikes and booze and being in the mountains.

The Crested Butte riders were living out their own mountain fantasy at the end of the road, largely beyond the reach of outside influence. And, for a short window in the 1970s, Crested Butte and mountain biking were flawlessly frozen in time.