A Humble Dream Shaums March Moves Forward by Giving Back

Words by Colin Wiseman

A single cord dangles from the ceiling of a nearly finished two-story house on the outskirts of Bellingham, Washington.

It’s tastefully low key, with an open floor plan. Sitting on a barstool at the kitchen island is mountain bike legend Shaums March, who’s talking about the handful of private trails he’s been roughing in as he puts down more permanent roots in this bike-centric town.

“This whole ridge, 27 acres behind us, is our property,” says Shaums, who lives here with his partner, Nicole Gerow, and two friendly pit bulls named Tucker and Kobe. “We started building a year before COVID and moved in right as the lock- down hit, which put a hold on everything, and we’re so close to being done now.”

Despite a high-profile presence during the early waves of freeriding, a celebrated downhill racing career, a coveted Red Bull contract and a pioneering role in developing a standardized mountain bike instructor training curriculum, Shaums manages to maintain an admirably mellow façade in the booming Pacific Northwest bike scene. In an industry filled with well-known personalities, he remains somewhat enigmatic—which is remarkable, considering his longtime media presence, multiple Rampage appearances and UCI World Cup success. Indeed, given his huge ongoing impact on mountain biking, his persona is borderline underground.

Now 46 years old, Shaums’ life thus far has been shaped by an itinerant childhood, a not-by-design career path and a drive to help others reach their full potential. His parents eloped to Haines, Alaska, in the 1970s, where they established a simpler existence at the end of the road. Shaums’ dad, Fred, found work as a deep-sea diver and dive instructor, and he supplemented their diet with freshly caught fish. His mother, Vivian, was a social worker.

“My parents were real-life nomads,” Shaums says. “They weren’t really into outdoor sports, but they were really into that outdoor adventurous life- style. In Haines, I think they were trying to get away from it all. We had a big garden, a few farm animals, chickens. We kind of lived off the land.”

But Fred left when Shaums was 6 years old. “He kind of disappeared,” Shaums says. “We never really knew where he was.”

That’s when they started traveling. Along with his sister Yolanda (the eldest) and brother Nuri (the middle child), Vivian took the family to the lower 48, bouncing between California, Texas, Washington, Pennsylvania and beyond. Shaums has a hard time remembering when and where and why they moved each time.

“[Vivian] would get these jobs and she’d say, ‘Hey, we’re moving to wherever.’ It was like, ‘OK, I guess we’re going,’ and we’d move towns and then she’d say, ‘Hey, where do we want to go next?’” Shaums recalls of each life-changing move. “So, as a family, we’d be like, ‘Let’s go to California,’ and she’s like, ‘OK.’ I remember driving into Santa Barbara, California, and we got off the freeway and drove along the beach. We were glued to the window, going, ‘We want to live here.’ So we pulled over.”

It was in Santa Barbara, during elementary school, when Shaums got his first bike. He was hooked, riding BMX and racing a bit. Despite every move his family made, bikes were a constant.

At one point they landed in a small town called Childress in north Texas, where Fred’s family was from. Shaums had a hard time there and got into trouble.

“It was kid stuff,” he explains. “There would be abandoned houses—it was Texas, right, there were abandoned houses everywhere. We’d hang out in them and we got busted for breaking down some walls.”

DESPITE EVERY MOVE HIS FAMILY MADE, BIKES WERE A CONSTANT.

He soon discovered he wasn’t very welcome there for other reasons.

“There was a bit of segregation,” Shaums says. “In Childress, there was the Black side of town, and I was an outgoing kid. My mom was white, Jewish, and my dad was Black. Moving all around from Alaska to Texas and Pennsylvania, I had friends of all backgrounds, but I quickly realized it mattered to other folks in Texas that I shouldn’t be on that side of the tracks.

“There were issues and I got in fights. I got chased and shot at ... and it was like, ‘Holy shit, ok, watch your back.’”

At this point, Shaums was 15 and very independent, and Vivian gave him an emancipation letter that said he could be on his own. He returned to Santa Barbara to live with his brother and found stability in school, friends, pumping gas and working at a pizza place.

By his senior year of high school, Shaums had transitioned to mountain biking. It was the early 1990s, and Santa Barbara had a nascent downhill scene with well-established shuttle trails. He rode them first on his brother’s Specialized Rockhopper, then a Bridgestone, which he promptly broke. His next ride had a suspension fork with 2.5 inches of travel, and he would ride it between Santa Barbara and Goleta—some 20 miles round trip—hitting urban features along the way. He took a BMX approach with a bit of suspension, bunny-hopping walls and doing foot plants off garbage cans, unintentionally developing skills and style that would shape his future as a professional rider.

Upon graduating high school, Shaums entered the local college’s mechanics program, allowing him to find work at a Midas Muffler and then Granny’s Garage, which focused on European imports. Then, in 1994, his roommate invited him to a cross-country race in Big Bear, California, where he laid eyes on the downhill course and immediately entered the race.

“People still were riding hard tails for downhill racing—full suspension came out the next year,” Shaums says. “The course was fire roads connected by pieces of singletrack. Big Bear was so fun. We loved it.”

By the next year, Shaums was racing most weekends at spots across California, moving up the ranks rapidly from beginner to intermediate to expert as his times improved.

“We were riding the same course as all the other categories, and by my second season of competing, in ’96, they put me in semi-pro because my times were in that range,” Shaums says. “It was a bit of a fight with USA Cycling to let me move up quick enough because they saw that I was beating my competition, but there was a wave of us new, up-and-coming riders beating their classes by a large enough margin, trying to find our natural competition. It felt like there was this group of us that for whatever reason were at that next level.”

One of these racers was John Kirkcaldie, from New Zealand, who became fast friends and even- tually Shaums’ roommate. They lived together in a warehouse, riding bikes and feeding off each other’s energy—a process that took their respective skills to a professional level. Shaums began racing in the pro category in 1997. There was a steep learning curve and he crashed a lot.

“I was in the top five of the pro series for every qualifying run, but I didn’t know how to race,” he says. “My mentality would be like, ‘Go as fast as you can,’ and I’d end up blowing up. Then in ’98 I got my head together, did more training—more mental training—and was able to start picking my spot back up into top five, top three.”

Ironically, the inspiration to explore the mental side of racing came from Shaun Palmer, the professional snowboarder and multisport athlete whose downhill racing style was notoriously loose.

“I was hanging out with Kirt Voreis and Palmer and a few others in Palmer’s bus in nowhere, Wisconsin, for one of those random races,” Shaums says. “[Palmer] was like, ‘March, you’ve just got to slow down. You’re just going too fast to make it down.’ And I’m like, ‘I guess you’re right.’”

HE WAS PART OF THE FIRST WAVE OF URBAN FREERIDE, BRINGING BMX-STYLE TRICKS TO HIS MOUNTAIN BIKE AND PULLING OFF STUNTS LIKE JUMPING OFF THE ROOF OF A SANTA BARBARA UNIVERSITY BUILDING. DESPITE WINNING A CALIFORNIA STATE DOWNHILL CHAMPIONSHIP, SHAUMS STILL WANTED TO HAVE A GOOD TIME.

Though Shaums was busy racing, his outgoing personality and fearlessness on a bike had earned him considerable media attention, including video appearances and multiple magazine covers. He was part of the first wave of urban freeride, bringing BMX-style tricks to his mountain bike and pulling off stunts like jumping off the roof of a Santa Barbara University building. Despite winning a California state downhill championship, Shaums still wanted to have a good time.

“I would be doing the jump comp that they had the night before the race and everybody’s like, ‘What are you doing? You could get hurt.’” Shaums says. “I’m like, ‘What do you mean? I’m here for the whole event.’ I’d party, be hungover, and somehow still do well.”

Eventually, Shaums recognized a need to improve his mental focus if he wanted to race downhill at the highest levels, and in 1998 a psychiatrist in Santa Barbara turned him on to hypnotherapy and meditation to harness what he now understands to be “severe ADHD.” He’d slow down his mind, his breathing and his frenetic energy on course, and this approach yielded results. He earned a couple of podiums in the National Off Road Bicycle Association (NORBA) series and finally got his first professional downhill victory at a NORBA race in Breckenridge, Colorado.

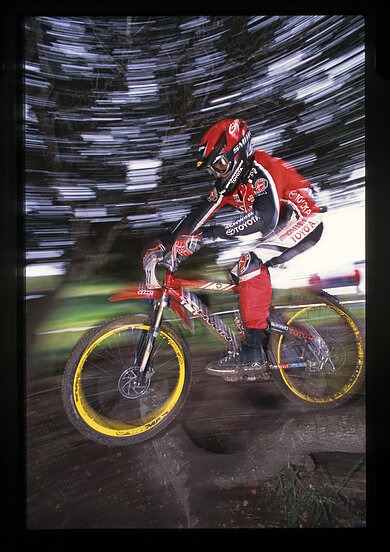

Despite grappling with injuries such as a hernia, a broken wrist, multiple shoulder dislocations and a whiplash fracture in his neck, Shaums had proven his racing talent, and it earned him a sponsorship with Schwinn—then a giant of the mountain bike industry. This meant a slot on the Schwinn-Toyota factory downhill racing team for the 1999 season of Union Cycliste International (UCI) World Cup events and a travel budget that would help him get to key races. But there was a fundamental problem.

“The bikes sucked,” Shaums says. “There had been a communication issue with the manufacturer in Taiwan and the head angles were all wrong.”

Shaums’ results suffered, and Schwinn sent him letters questioning his performance and threatening to drop him from the team. He says he felt serious pressure and the experience was anything but fun. Toward the end of the year, the company sent him a bike with workable geometry and he managed to crack the top 20 and salvage the season. Then, the very next spring, he got into trouble for extracurricular activities at the Sea Otter Classic festival near Monterey, California. Schwinn made a corporate-level decision to drop him from the team, and Shaums walked away from professional downhill racing temporarily.

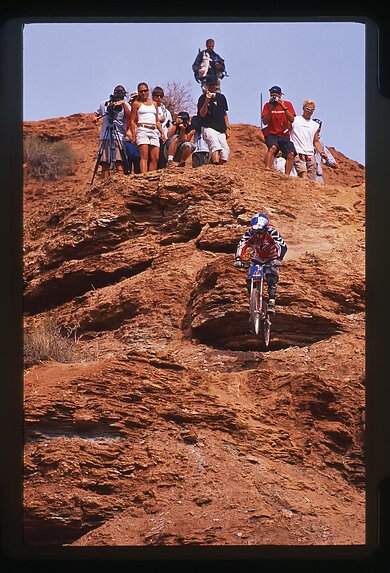

Still backed by Red Bull and a handful of endemic brands, Shaums remained in front of the lens as a freerider and began testing for Chumba Bikes. In 2000, he moved to Squamish, British Columbia, got married and bought a house. His life continued to revolve around mountain biking and he competed in the first five Rampage events, registering an impressive fourth-place finish out of 28 riders in the second Rampage in 2002. Ever humble, however, Shaums downplays these performances.

“It was more of a gathering than a contest at that point,” he says.

Over the next several years, Shaums raced sporadically, even traveling to Europe and spending an hour in the hot seat at the World Championships in Åre, Sweden. He never lost his skill, as evidenced by his back-to-back wins at the UCI Masters World Cup Championship at Sun Peaks, British Columbia, in 2006 and the following year at Pra Loup, France—when he entered the race on a whim after encouragement from one of his protégés.

All in all, the early 2000s were a time of immense change for Shaums and he realized he needed to return the focus of his mountain biking life to fun. And one of the main ways to do this was something he’d discovered a few years earlier: helping others through teaching. As early as 1998, he’d started Mad March Racing in an effort to help fellow racers scout courses for lines and develop their plans of attack.

“Being that outgoing person with the media presence, people would recognize me,” Shaums says. “I’d do a lap with them, then they’d ask if I was walking the course at a race, and we’d do it together, I’d point out lines. That evolved into clinics where we’d work on braking and cornering, just my own curriculum.”

Upon moving to Squamish in 2000, Shaums earned his instructor certification, which he says brought his clinics to “a new level.” He began coaching future World Cup downhill standouts such as the late Stevie Smith, Miranda Miller, Lauren Rosser, Duncan Riffle, Richie Rude and Danny Hart, first on his own and then through Cycling BC and the Canadian Cycling Association. He loved it and his athletes became family.

“My mom had shown me that it’s all about helping others,” Shaums says. “That makes the world go around—being nice and doing good to others or treating others as you’d like to be treated. It makes you feel good. It makes others feel good. So many people helped me along and I want to do the same.”

Given the caliber of athletes Shaums was coaching, he realized he needed to up his game even more. Problem was, there wasn’t an established higher-level coaching curriculum.

“I was like, ‘Where’s the level 2 [certification]?’” Shaums remembers. “There wasn’t one. The progressions in the initial certification didn’t go very deep, and here I was working with high-level athletes. I could understand and teach a certain amount of it based on my personal knowledge from riding and racing, so we decided to develop a curriculum.”

Together with fellow mountain biking ambassadors such as Canadian trials rider Ryan Leech and Vancouver-based freerider Jay “Hoots” Krantz, Shaums worked to expand the Canadian Mountain Bike Instructor Certification (CMIC) to include advanced skills and progressions. At that time, the program was run by its two founding Canadian athletes, trials rider Joan Jones and downhiller Daamiann “Daamo” Skelton. The two had been developing a more effective way to train instructors, to spread the stoke of riding from the top down. But other coaching programs had mimicked their formula and by 2009 they’d had enough.

Shaums purchased the rights to the certification program and quickly set about expanding what would later become the Bike Instructor Certification Program (BICP). He franchised his original business, Mad March Racing, and before long there were multiple locations from coast to coast, with more than 20 instructors helping to run events nationwide. Shaums wanted everyone to progress, and he’d visit the various franchises once or twice each year to host clinics. By 2013, the certification program was running relatively smoothly and growing in several countries.

“The pedagogy of it is really physics-based and that’s something that I believe in,” Shaums explains. “Understanding the physics and being able to do a lot of the advanced moves allowed me to break them down. Having that base structure that Joan and Daamiann brought to the table made it much easier to keep growing it and we just kind of stayed to that pattern.”

“MY MOM HAD SHOWN ME THAT IT’S ALL ABOUT HELPING OTHERS. THAT MAKES THE WORLD GO AROUND—BEING NICE AND DOING GOOD TO OTHERS OR TREATING OTHERS AS YOU’D LIKE TO BE TREATED. IT MAKES YOU FEEL GOOD. IT MAKES OTHERS FEEL GOOD. SO MANY PEOPLE HELPED ME ALONG AND I WANT TO DO THE SAME.” - SHAUMS MARCH

The road to expanding the curriculum was not altogether smooth and Shaums encountered imitators along the way.

“Trying to keep our curriculum ours has been the hardest piece,” he says. “We’ve seen multiple organizations get one person certified and then take our whole manual and copy it, right down to the photos. They’d change the cover and that was it. We had lawyers send cease-and-desist letters and those kinds of things.

“But for the most part, nobody really wants to go in and start doing it themselves, so that’s why they take the best thing they can find and try to make it theirs,” he adds.

In 2014, Shaums’ marriage was ending. With his two children, Isaac (now 15) and Asia (now 13), remaining in Squamish, he moved to Bellingham so he could stay close to them. Both Isaac and Asia ride bikes, and Isaac pushes the limits, having sent Whistler’s infamous Crabapple Hits jump line at the tender age of 11—a fact that Shaums relays with equal parts pride and concern.

Shaums sold the certification course to the International Mountain Bicycling Association in 2013, only to buy it back in late 2017. About that time, he was joined in Bellingham by his current partner, Nicole Gerow, who now works as BICP’s executive director. She also runs the kids camps for March Northwest, Shaums’ Bellingham-based skills-clinic company.

“[Shaums] is very determined and focused on many different things all at once,” Nicole says. “When I met him, he’s like, ‘I’m a mountain bike coach,’ and I was like, ‘So what.’ I didn’t really get it until I saw him with his customers, his people, and understood that everything Shaums does is connected to such a love for mountain biking. And that passion just pours out to these people.”

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Shaums has changed course a bit, taking a day job with a building firm called Dawson Construction since he couldn’t travel or teach in person with any regularity. And with BICP continuing to grow as a nonprofit organization, with two dozen instructor trainers, 100 courses per year, three levels of certification and representatives in more than 16 countries, he’s increasingly able to focus more on local coaching work.

“The certifications are way bigger than me now,” says Shaums, who serves as BICP’s president. “My long-term goal would be to have the Northwest, Bellingham, host a national or World Cup event, while grooming the next local Olympic athlete.”

To this end, Shaums recently began working with a youth racing team alongside Bellingham bike dad Dave Simeur and a few others. There are 52 kids on the team, with at least 40 of them from Bellingham, and a few come from as far as Leavenworth, Bellevue and Bainbridge Island.

“They come because of Shaums,” Simeur says. “He puts them through 18 clinics, and the kids are just drawn to Shaums. He has such a great smile— it’s genuine. He has this way of connecting with people from all these different cultures. He’s able to teach them without being judgmental.

“It’s really positive and really cool and it’s sincere,” Simeur adds. “You can’t fake that. He’s just a great role model for the kids. He’s a big kid himself.”

While Shaums is cautiously optimistic about getting back into more traveling, more camps and more coaching, for the time being he’s enjoying the flexibility that allows him to ride often, right behind his house. He’s manifested a humble dream.

“Helping people gives me direction,” he says. “It’s so gratifying. Watching someone go through the process of getting better, owning it and learning to play and succeed—I get to do that through riding bikes. I can’t think of a better way to spend time in this world.”