Hungry Eyes A Singletrack Feast in the Idaho Panhandle

Words and Photos by Aaron Theisen

When the eyes of a small-town bike mechanic light up and then go far off and dreamy when talking about a local trail, you listen.

Brian Anderson at Greasy Fingers Bikes N Repair, in Sandpoint, Idaho, is pointing at a collection of pins on a wall mounted map of north Idaho. In Brian’s parlance, there are two types of worthwhile trails: bitchin’ and super bitchin’. The pins clustered around Canuck Pass, near the Canadian border, highlight a trail that falls into the latter category.

Sandpoint is a timber-and-tourist town on the shore of Lake Pend Oreille, one of few communities of any size in the so called Idaho Panhandle. Squeezed between Washington and Montana, bounded by the Selkirk Mountains to the west and the Purcells and Cabinets to the east, the Panhandle has always acted as an antenna for folks looking to escape civilization. It’s a good place to get lost.

Looking for a quick dose of alpine riding close to my home in Spokane, some 90 minutes from Sandpoint, I had zeroed in on the Panhandle. The trails here had been on my radar for years, but, as backyard trails tend to be, they were always bypassed in favor of the famed Kootenays immediately across the border in British Columbia.

The Kootenay River turns to the Kootenai when it crosses the border, and with that one-letter swap comes a change in the character of the mountain ranges surrounding it. Ranges that push past 9,000 feet up north barely scrape 7,000 down south. In the same way, the world-class Kootenays riding morphs into something diff erent here—more horizontal than vertical, more about exploration than adrenaline.

But an extensive system of ridge-running trails looked like it had potential, and the area’s proximity to home allowed a group of six of us to come and go as work and life schedules permitted.

Pointing at the trails off Canuck Pass, Anderson told me the Forest Service had been putting in work to make their backcountry trails a little more friendly to bikes—cleaning up tread, opening up switchbacks, widening exceedingly narrow sections. The eff ort was partly in response to the loss of access to a handful of classic rides that crossed wilderness study areas, and partly an outgrowth of passionate locals such as Anderson.

The effort was immediately apparent on Ruby Ridge. Having camped at the pass, we’d already sampled the riding on an out-and-back along Keno Ridge—thick subalpine forest interspersed with pocket meadows, all prime grizzly habitat, as Forest Service signs warned us regularly. But despite Anderson’s stamp of “super-bitchin’” approval, Ruby Ridge exceeded our expectations. Over the course of 4,000 vertical feet of shredding loam and surfing scree shards that pinged off our downtubes, our yells of “Heyyyoooo!” served both as our own stamp of approval and as grizzly bear deterrents.

A handful of long, shuttle-able descents off a paved mountain road with amazing views? We couldn’t believe our luck.

The Panhandle rarely rewards riders this easily though, as we discovered the next day on the Beetop-Roundtop trail, east of Lake Pend Oreille.

On paper it looked like a mellow ridge run tightly hugging the topo map’s 6,000-foot elevation line. On the ground, it was another matter entirely.

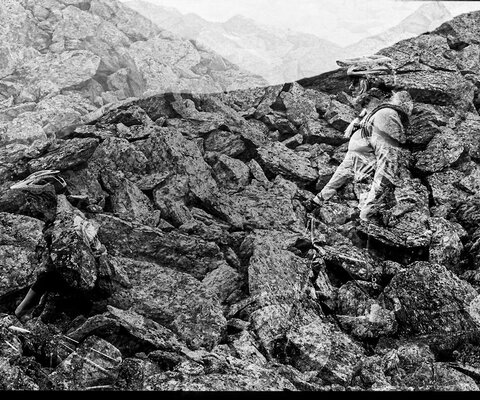

On a trail narrow enough that the pins in our pedals acted like hedge trimmers, we pinballed our way down steep sidehill descents and shouldered our bikes across slide paths of exfoliated bedrock, laughing as we kept a running tally of who’d taken a slow-speed tumble down the mountainside.

“Everything on this trail seems to want to reach out and grab you,” shouted one of my group as he clipped a pedal on a rock obscured under a tuft of bear grass. I didn’t tell him Anderson had warned me of just that in his merely bitchin’ assessment of the trail.

As we dozed on the rocky summit of Roundtop though, looking over the nearly 70-mile-long Lake Pend Oreille more than 4,000 vertical feet below, I saw on my riding buddies the same expression that Anderson had shown. I realized that, even if it doesn’t come easily, sometimes your eyes can get that far-off look while staying close to home.