Welcome to Issue 14.3

We’re living at a time when the pace of change is unprecedented in human history, and this is certainly the case within the rapidly expanding world of mountain biking. Our new Issue 14.3—themed around the concept of “progression”—reflects key changes to our sport as well as inherent obstacles to its continued evolution. Our cover feature chronicles the meteoric rise of the women’s freeride movement through the all-female Formation event, while also highlighting fundamental challenges to its future development. We take an in-depth look at the pressing problem of affordable housing shortages in mountain bike towns across the United States, outlining the creative ways that communities are addressing a dilemma that affects so many of us. And with stories covering the extraordinary ascent of New Zealand freerider Robin Goomes, the far-reaching impact of master trailbuilder Valerie Naylor, and the paradigm-rattling vision of photographer JB Liautard, there is abundant inspiration for breakthroughs big and small. Issue 14.3 is your antidote to angsty mediocrity.

As the dust settled in Virgin, Utah, following the final runs of the May 2022 iteration of Red Bull Formation, the energy at the venue was soaring.

Not only had many of the 12 female participating athletes just stomped the biggest lines of their careers on some of the most high-consequence terrain they’d ever ridden, but it looked like some of them were finally going to get a shot at what they’d been working toward for years: a slot at Red Bull Rampage, a competition widely viewed as the pinnacle of freeride mountain biking, and one to which a woman has never been invited since its inception in 2001. In a private meeting, Red Bull representatives had told a select group that a women’s category was on the horizon. The hope was to announce this at Rampage in October 2022, then add the category in 2023.

“I was so motivated,” said Casey Brown, a decorated freerider who first started eyeing Rampage more than a decade ago. “I was like, ‘Yes! This is amazing. We have over a year to prepare for this, and I think that’s what everyone focused on. [Red Bull] has the reins, it’s headed in the right direction, let’s get back to our riding. Let’s make sure our riding’s sick, and when it comes around, we’ll be ready. That was a huge motivator. I shaped my whole year around it.”

Words by Nicole Formosa | Photos by Katie Lozancich

Jeremy Grasby gets a little nostalgic whenever he rides past the yellow gate and enters the labyrinth of singletrack that is the Cumberland network. It’s short-sleeves weather. Trillium flowers are blossoming in the forests of Vancouver Island while the western toads croak their horny approval of spring’s arrival. There’s even a puff of dust in the air as Grasby rails a tight right-hander on Bear Buns, a local classic.

The trailhead parking lot was already halffull on a mid-week morning when he spun past half an hour earlier. It’s a testament to the fact that Cumberland singletrack—120 miles of it and counting, virtually all built on private forest land—is among the most used networks in North America according to online trail mapping resources.

What a journey it’s been.

Words by Andrew Findlay | Photos by Haruki "Harookz" Noguchi

The ability to make something complex seem simple is a sign of true mastery, whether in athletics, the arts, or everyday life. This is especially true when it comes to creating images and in the world of mountain bike photography, JB Liautard has consistently shown a penchant for pushing the envelope.

In a professional career spanning less than a decade, the passionate young Frenchman has made a name for himself through his imagi- native yet methodical approach to producing images that capture the sheer essence of a moment, blending it seamlessly with the majesty of its surroundings. His fascination with light, landscapes, and motion—and the challenge of harnessing all three into a single harmony with timeless resonance—has led to an ever-mount- ing portfolio of unforgettable images that straddle the line between reality and fantasy.

Words & Photos by JB Liautard

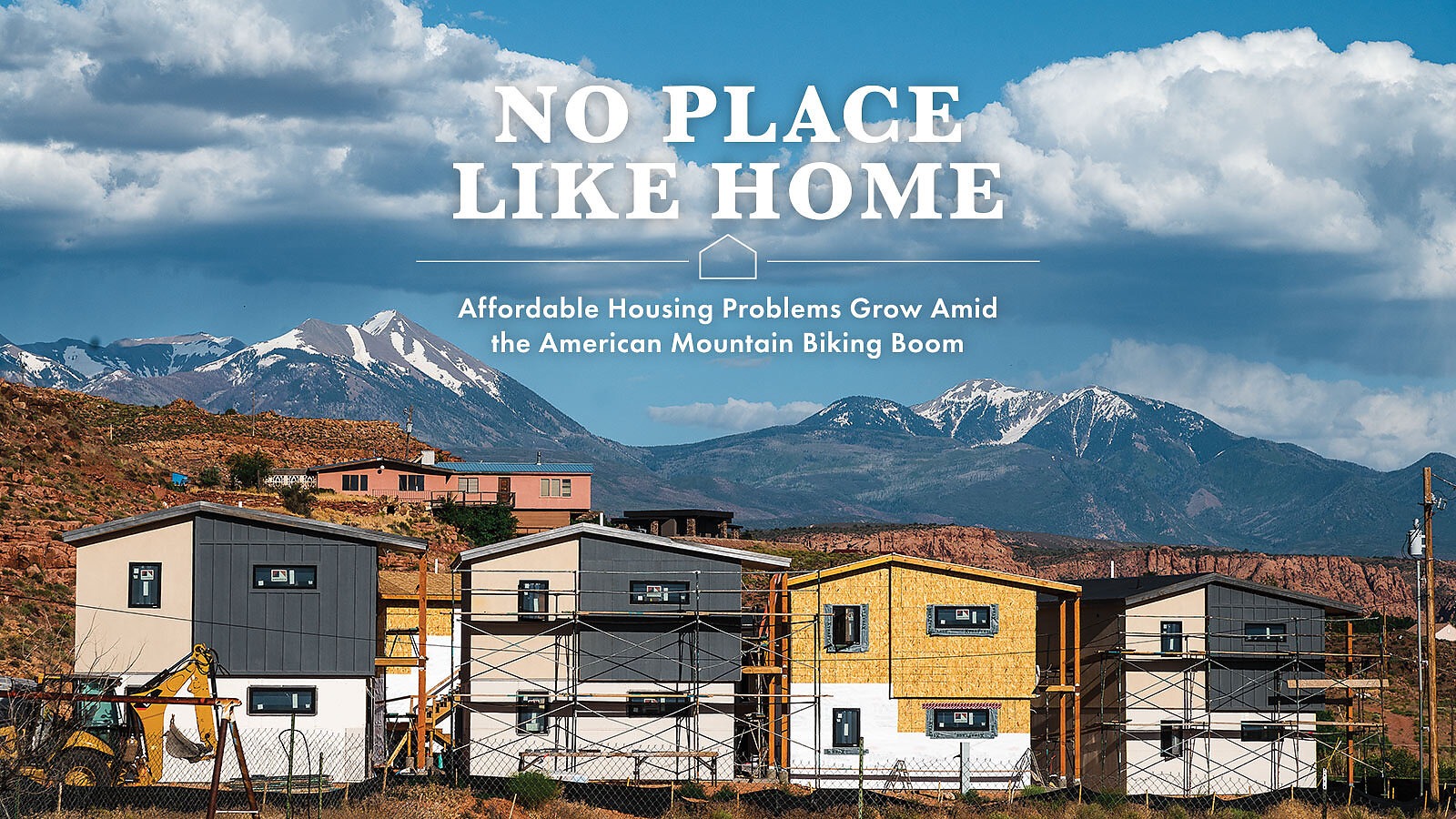

Chad Cornish doesn’t want to leave Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley. Originally from upstate New York, Chad, 34, moved to the valley 10 years ago. Back then he was a skier, and what better place for a skier to live than the base of Aspen and Snowmass Mountains? But when he rode Government Trail for the first time, he saw a Roaring Fork Valley beyond the resorts, one that was “tough, beautiful, desolate.”

The Roaring Fork Valley is one of only six gold-level International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) Ride Centers in the world. With over 300 miles of singletrack in the valley between Aspen and Glenwood Springs, Chad has no shortage of trails to ride. Life in the valley is pretty sweet. It’s where Chad settled down with his wife, started their family, built singletrack for the county, and taught his daughter to ride a bike. But Chad often feels cynical about the current state of housing in the valley, especially where he lives in Aspen. It was expensive before the pandemic. Now, even condos cost an average $2.5 million.

Words by Jess Daddio

Spectators pack like sardines along the iconic Dream Track in Queenstown, New Zealand and fixate on gargantuan gap jumps that weave down the hill and out of view. To mountain bikers, these 60-foot features are works of art. Mounds of earth sculpted for flight, they were initially built for the “New World Disorder 5” film in 2004.

Now, they’re one of the biggest public jump lines in the world. And, on this day, a frenzied crowd is gathered to watch as hordes of riders drop in for the annual McGazza Fest jam session, each airing big on every feature as the late Kelly McGarry would have done. One rider who stands out as she whizzes by is Robin Goomes. With each lap, the Kiwi teases a new trick: a nac nac, a tuck no-hander, a t-bog, just a few to name.

As she hikes back up to the start with pal Harriet “Haz” Burbidge-Smith, she’s beaming, or as she’d put it, “frothing.” Jumps like these are her natural element, which isn’t shocking considering her impressive riding resume: 2023 Crankworx Rotorua Speed and Style winner, 2021 Crankworx Whip-Off champion, one of the first women invited to DarkFest, and the first woman to backflip in a Crankworx competition. What is shocking is that Goomes has only been riding for six years.

Words by Katie Lozancich

Within a week of showing up in Bellingham, Washington in 2012, it was made very clear to me that I needed a mountain bike.

I had moved for a five-month internship at a local magazine—I was barely 21 and on the kind of early-20s tear that can only result from being raised in a rural town with eight churches and little space for trouble. That summer opened a lot of doors for me, but mountain biking was admittedly not one of them.

My colleagues at the magazine were the first people to encourage me to try mountain biking. I had about $300 to my name, part of what I’d saved prior to leaving Michigan for the internship; obviously this wouldn’t get me far in Bellingham, even in 2012. The first of the month was fast approaching, and while the questionable $250-a-month room I’d found on Craigslist wouldn’t completely break the bank, I wasn’t in a position to be taking up new hobbies.

Words by Amanda Monthei | Photos by Cy Whitling

Valerie Naylor is the Rock Queen. At least, that’s what Randy Conner of Contour Trail Design Company calls her. He’s seen her move rocks that weigh more than an excavator.

“I don’t know how she didn’t knock herself and the machine off the side of the hill,” Conner said, recalling a time at Concord Park in Knoxville, Tennessee when Naylor was lead machine operator on a project. “[The rock] was probably eight feet long, four feet across, a foot-and-a-half thick, and she just dragged it down the hill and dropped it straight where it was supposed to go. It’s like she makes up her own physics.”

There are no rocks at Naylor’s latest project, a half-mile of flowing trail in Knoxville’s I.C. King Park. At her job site early this spring, Naylor made quick work of the open hardwood forest, combing through duff with deft strokes of the mini excavator’s thumb. Although Naylor loves the intricacy of a technical build, that’s not why she’s a trailbuilder. The 52-year-old cyclist has been designing, planning, and constructing trails for nearly two decades. No matter the project, be it lift-serve lines in the Swiss Alps or rock sidewalks at Jake’s Rocks in Pennsylvania, Naylor feels it’s enough to know that any trail she creates will bring joy to others.

Words by Jess Daddio | Photos by Leslie Kehmeier

Since getting my first mountain bike in 1990, I’ve seen the ill effects of what ambulance chasers have done to our sport. Closed trails, helmet laws, and a myriad of neon warning stickers covering every component on a new bike just scratch the surface of how the legal system has infiltrated mountain biking.

Don’t get me wrong; justice should be served to irresponsible brands for making unsafe products. But winning a lawsuit for millions for being hit by a car in the middle of the night and blaming it on the bike’s “faulty reflectors” is questionable. Surely, one of the reflectors had to work before the claimant— who had no lights and was wearing black clothes— became a hood ornament. The “faulty reflectors” guy became the frivolous lawsuit ire of every bike brand and enthusiast in the cycling industry until the “faulty quick release” guy came along in thedays before disc brakes and through-axles. That “faulty quick release” guy was almost me.

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Victor Brousseaud

I emerged from the desert at the trailhead, riding through the parking lot, avoiding eye contact with everyone. I was fuming and nobody needed to experience my irrational rage. I had just finished riding one of my favorite trails, only to discover it had become a victim of the dreaded “trail sanitation.”

This phenomenon happens when well-intentioned volunteers smooth out obstacles on a trail in the name of maintenance, consequentially making it easier.

I know there are legitimate reasons for trailwork. It’s necessary to repair erosion, prevent siltation in the watershed, and protect habitats. And many volunteers and trail crews are nothing short of modern saints. But why did it have to happen to this beloved trail of mine?

Words by Chris Reichel