Welcome to Issue 14.4

We at Freehub believe the bike is the ultimate tool for adventure, whether it’s the medium for exploring some far-flung corner of the planet or simply for discovering what’s beyond that next turn on the trail. Every year, we celebrate the wonderful utility of two wheels with an entire issue dedicated to adventures of all shapes and sizes, as viewed through the lenses of the world’s most inspired writers and photographers. In our cover feature, we take an in-depth look at the life of Canadian soul rider Matt Hunter, who over the past 20 years has become the very embodiment of everyday adventure—and, in the process, has come to represent key intangibles of what it means to be a mountain biker. And we showcase the sheer beauty of trails—from the Austrian and Swiss Alps to Tasmania and the Bolivian highlands—while also examining how personal bonds are strengthened through overcoming the hardships inherent to these rugged places. Welcome to your next adventure: Issue 14.4.

A single uphill pedal strike could be disastrous. Focused minds make sharp decisions.

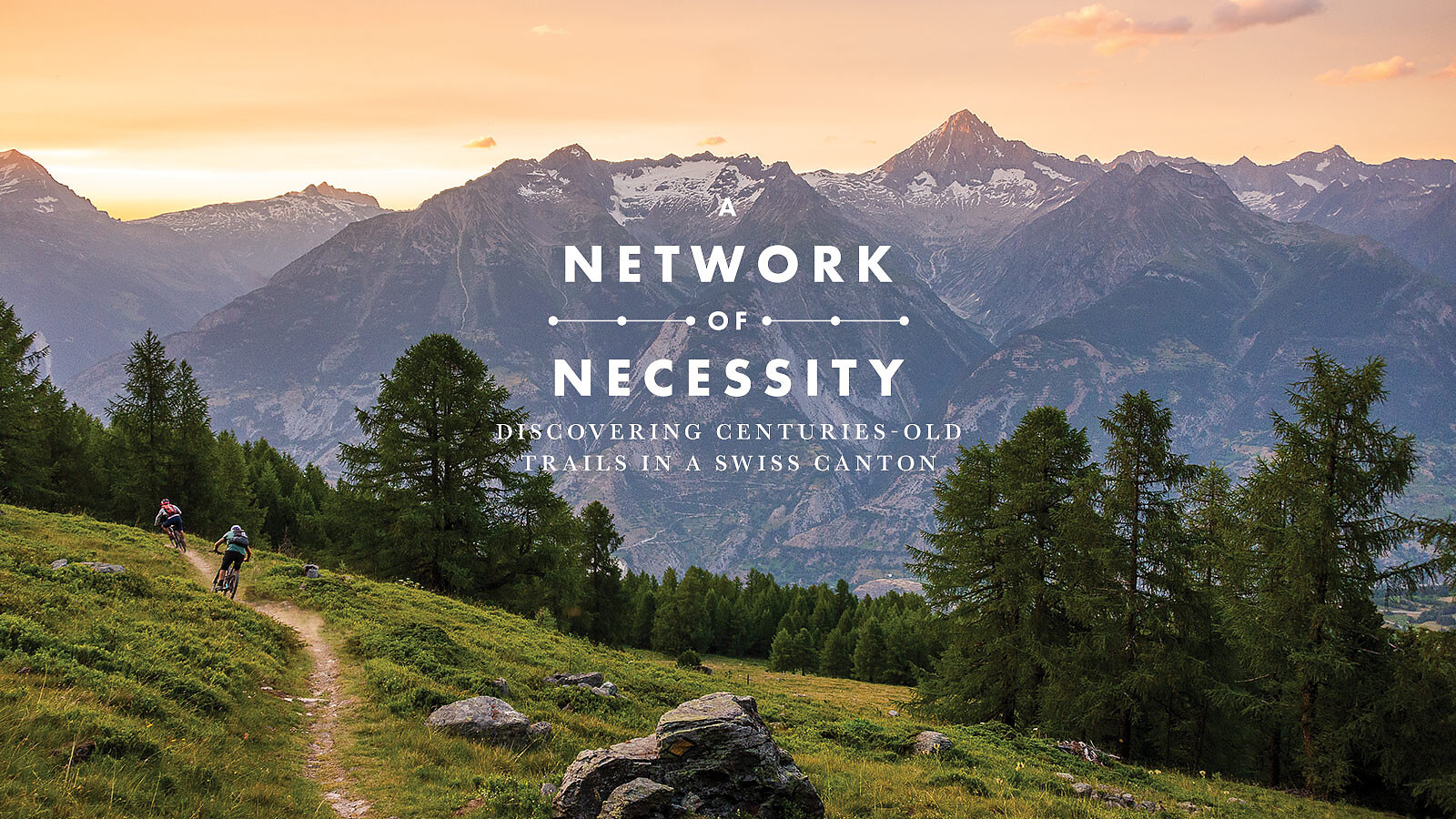

“If you fall here, you don’t dead,” says Christian Ammann in his blunt, grammatically unique English.

Coming from a stoic, Swiss-German farmer turned mountain bike guide, this amounts to encouragement. More than a vertical mile of white-knuckle descending below, the slate roofs of Stalden, Switzerland glitter in the sun next to the Matter Vispa river, swollen and coffee-colored with glacial melt driven by a record-breaking heatwave cooking Europe.

A few minutes earlier, and a half-dozen tight switchbacks above, we had left 80-something mountain guide Elmar Brigger sitting on the patio of Restaurant Jägerstube, his cliffside retirement project. With some prompting, he had tooted out a solo on the alpenhorn—he was rusty—before pouring a round of home-distilled apricot schnapps. It was delicious and made for a dose of well-timed liquid courage.

Words by Andrew Findlay | Photos by Kari Medig

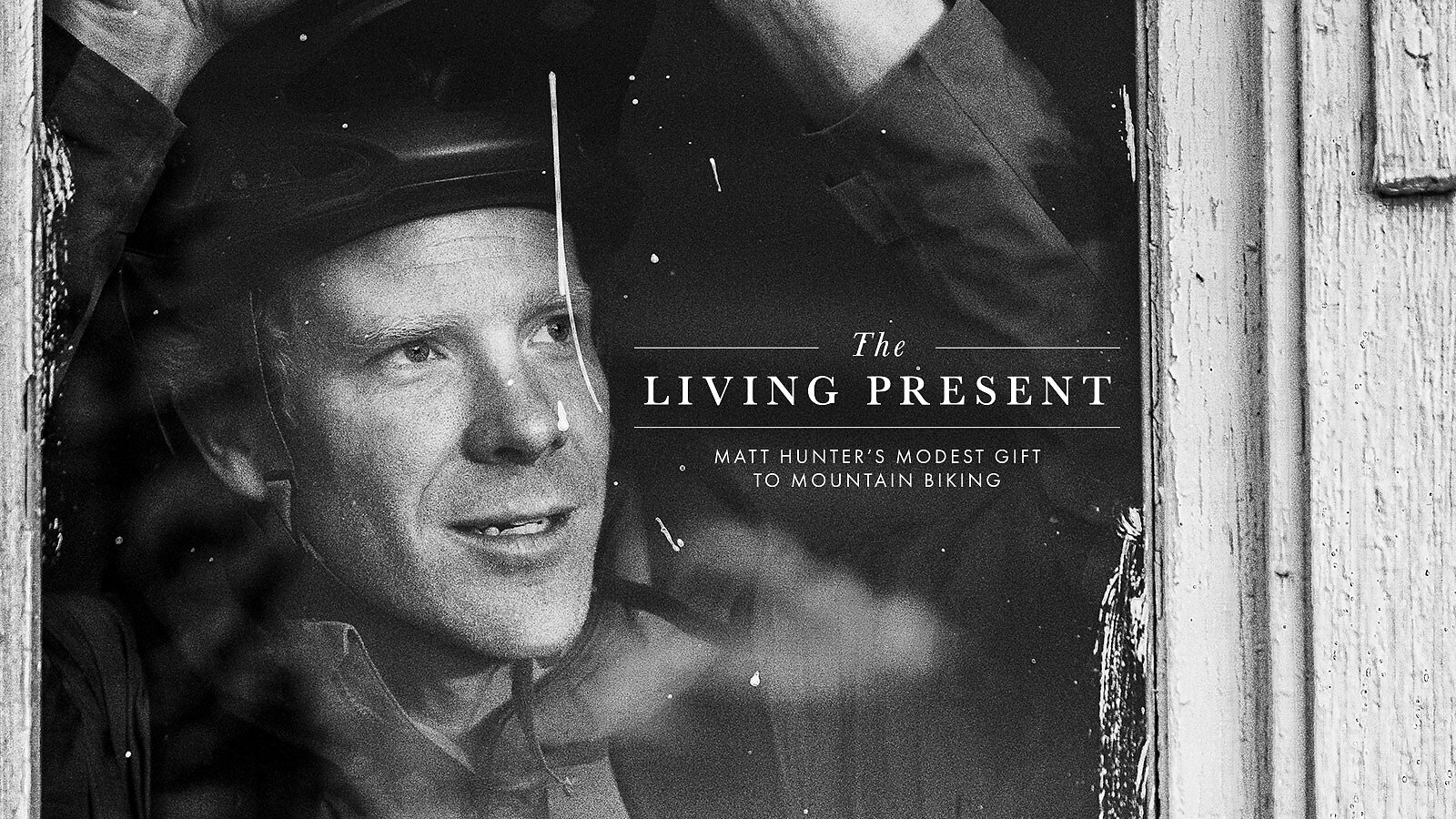

Thick sheets of snow are whipped sideways by a stiff wind sweeping across a rocky mountainside. Little can be heard above the howling gusts that have driven a dispirited team of adventurers into tents barricaded by windbreaks of stacked granite slabs. It’s June of 2013, and the riders are 11 days into what they hope will be a world-first mountain bike traverse of Afghanistan’s otherworldly Wakhan Corridor.

With several 16,000-plus-foot passes remaining to be crossed, the unrelenting whiteout conditions have some questioning whether the mission will be possible. Morale is ebbing toward the lowest point of the expedition. Suddenly, a lighthearted chuckle echoes through the camp, followed by the hasty unzipping of a tent fly. Barely visible through the blizzard, Matt Hunter emerges, beaming with the contentment of a monk who has just achieved another level of enlightenment.

“Whoa, dudes, it’s coming down!” he laughs excitedly, pointing at the dark clouds obscuring the 16,416-foot-high Karabel Pass the crew had hoped to negotiate by late afternoon. “It’s like 2 p.m. and we’re just hangin’ out in the tents!”

Words by Brice Minnigh

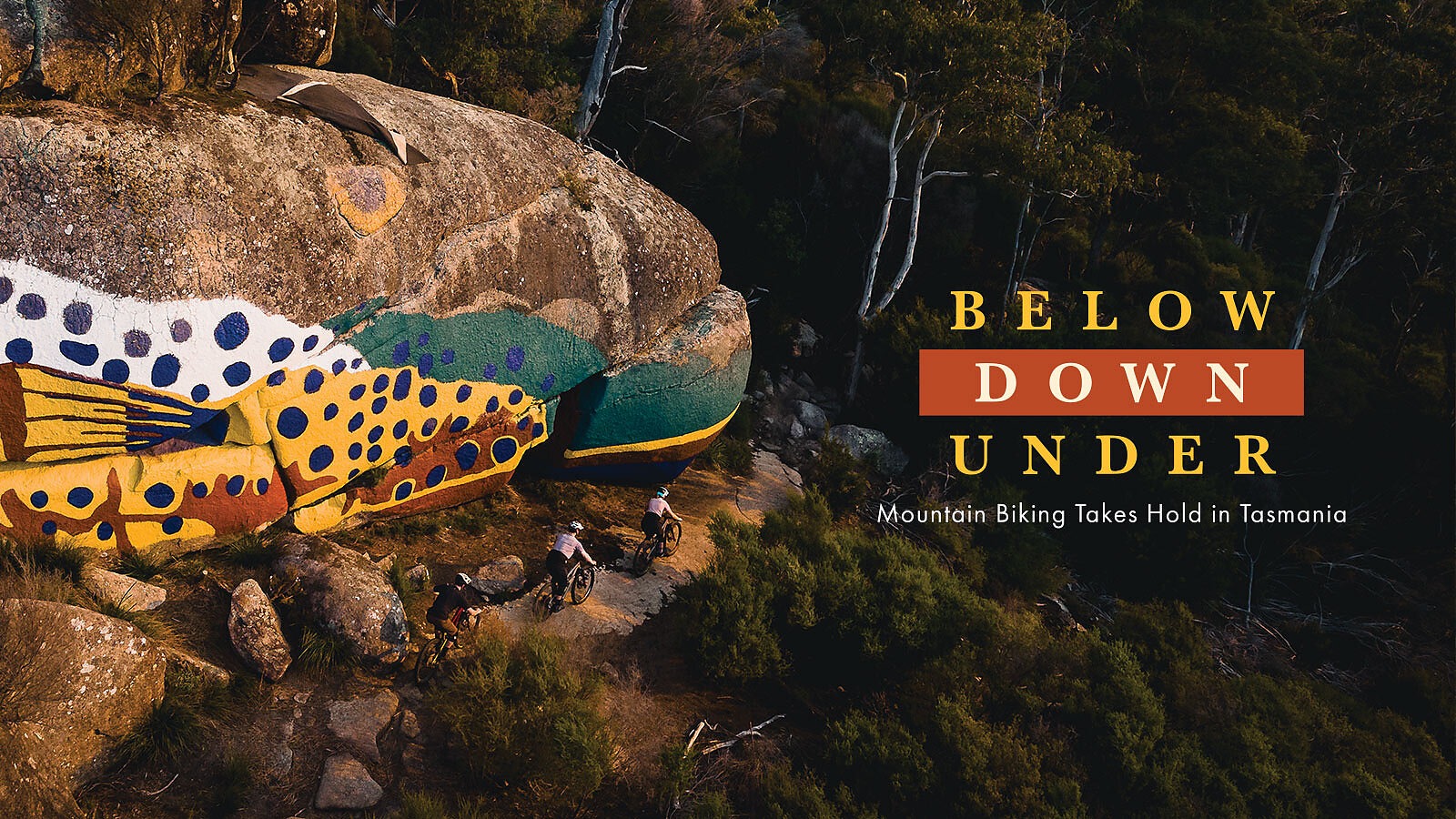

It’s the state Australia forgot: a small island sitting far off the southernmost point of the mainland, exposed and truly wild. It’s a land of immense wilderness, rugged landscapes, and pristine coastlines—a place where trees grow to 100 meters tall and a home to many indigenous plants and animals that don’t exist anywhere else in the world.

Once part of the supercontinent Gondwana, Tasmania is a time capsule of a prehistoric wonderland. The southern hemisphere’s last temperate rainforest exists here, serving as a reminder of the dense growth that once covered lands in this far-flung part of the globe. Although she’s often the blip left off of maps, this space has allowed Tasmania to—culturally and environmentally— evolve without much interference.

Take a step away from the glare of the golden sands, look beneath the towering trees, and you’ll find undisturbed forest floors crawling with wildlife and now, an increasing number of mountain bikers. For observers of mountain bike culture, it would be easy to sit back and assume that Tasmania’s singletrack renown is a by-product of publicity gained from hosting events such as the Enduro World Series. In reality, this island state of Australia has been building its scene for decades through a mix of meticulous planning, tireless work by key community members, and advice from a few trusted consultants with a gift for convincing government officials to take a chance.

Words and Photos by Cameron Mackenzie

There is an awful lot of pride among mountain bikers along the eastern seaboard of the United States in relation to the word “jank”— especially in the northeastern peninsula of New England.

Originally a term used to convey the convoluted nature of roots and rocks that embody trails whose personalities skew toward an especially technical and thought-provoking nature, the word now stretches to describe the design mindset employed by many of New England’s builders who strive to maintain the area’s raw character.

The trails that have come forth from this dance between person and place have, in only a few decades, made the region a destination for Enduro World Series rounds, fostered countless budding riding scenes, and even transformed the local economies of some small towns by providing yearround tourism. New England has cracked the code of creating trails for riders of all abilities, a magic ratio of rolling cross-country networks, technical downhill tracks, and community connectedness that is being replicated elsewhere—something to emulate for those locales proclaiming themselves to be “Mountain Bike Capitals.”

Words by Dillon Osleger | Photos by Mark J. Clement

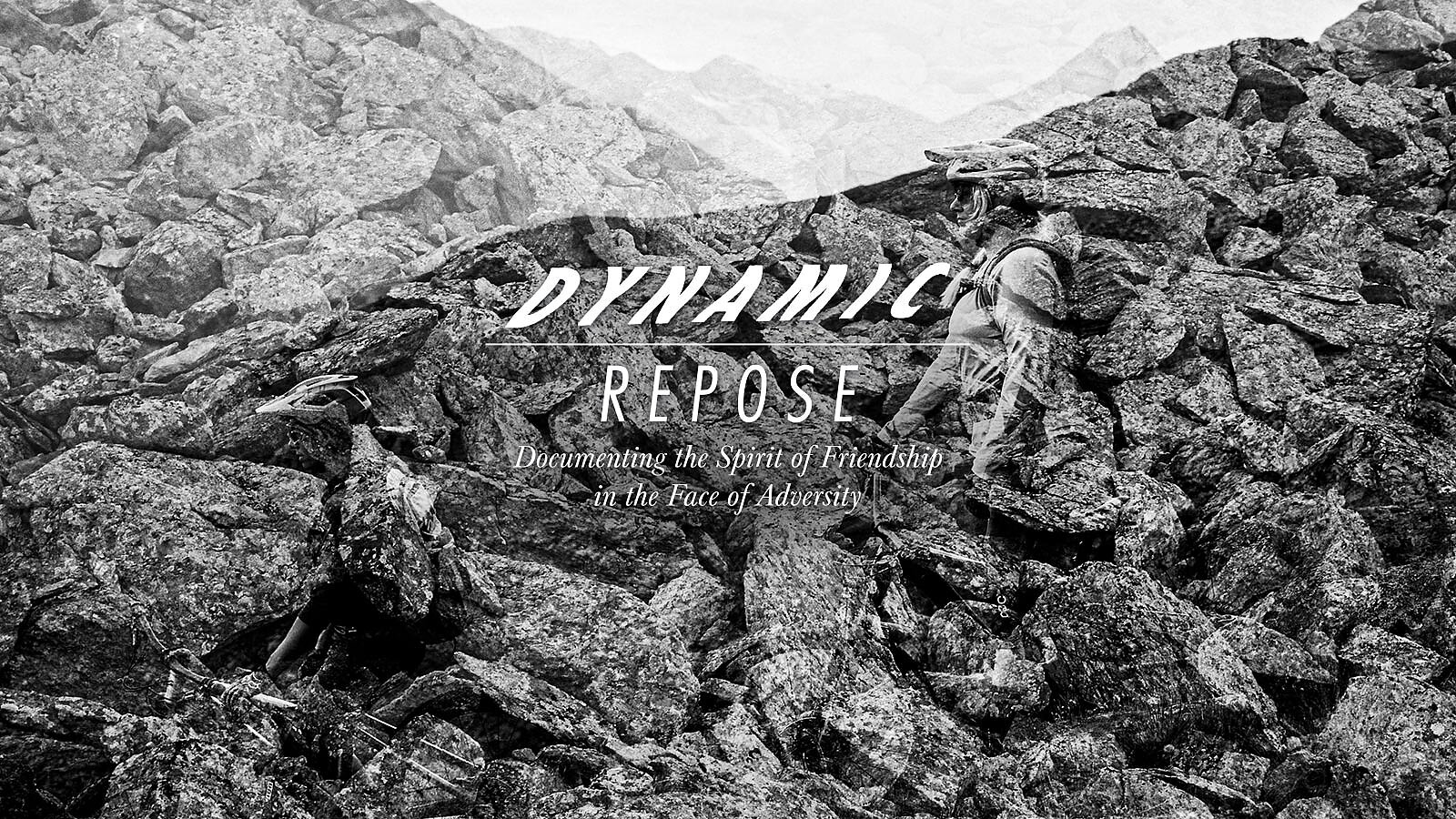

One of the most profound facets of the human condition involves the act of pushing oneself beyond the boundaries of comfort. Delving into the outermost limits of what an individual may consider possible offers opportunities for gaining insights, enhancing mental and physical strength, and even experiencing spiritual epiphanies.

Feeling called to examine this transformative process, Spanish photographer Carlos Blanchard employed the traditional medium of film to document friends Verena Hennes, Mary Irrasch, Eva Danner, and Maria Frykman-Grant on a trip in the Ötztal Alps near the border of Austria and Italy. The resulting images—some of which were shot as multiple exposures—immortalize the journey of four individuals as they challenged their thresholds for discomfort amidst rugged terrain. Blanchard’s gallery, accompanied by diary-like entries from each of the women, mixes moments of reflection with the hardship of ascending mountain passes and taking on treacherous descents. At the end of the trip, the photographer found himself moved.

“As a group, and each of them as individuals, had the courage to not only offer help to others when they needed it, but to open up with their thoughts and fears throughout the route,” Blanchard said. “It’s an interesting exercise that could teach us something about how to lose the fear of accepting our weaknesses and vulnerabilities to others.”

Photos by Carlos Blanchard

When settlers first came to the Pacific Northwest, they began an initiative for deforestation. The forest held many valuable resources, but it also evoked fear in people, which, in turn, evoked a desire to tame it. Perhaps, as a species, nothing is more ingrained in us than the inherent understanding that nature holds the capacity to both nourish us and rip us down to our very core.

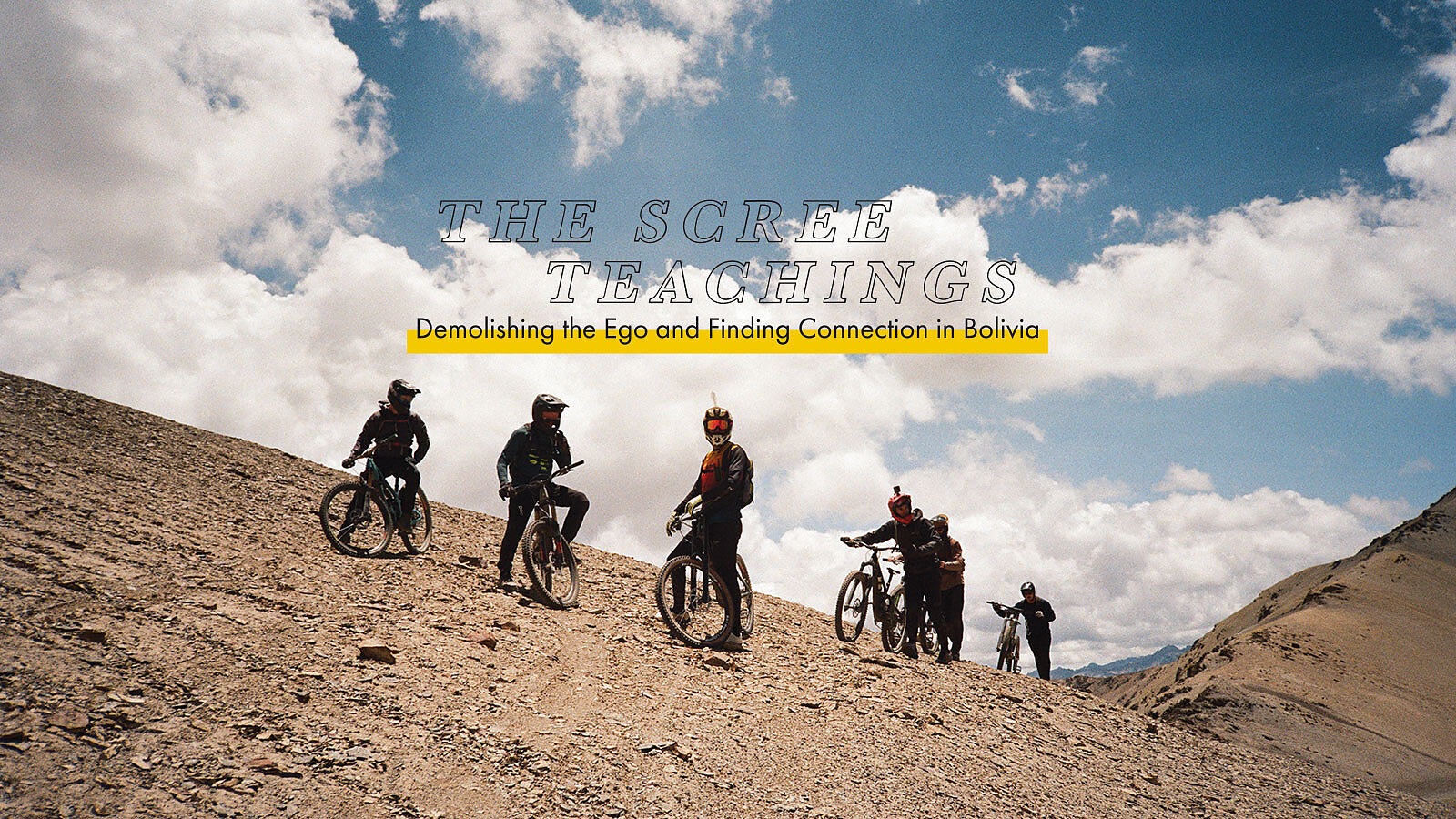

With much deference to this idea, I traveled last February from Bellingham, Washington to Bolivia where, alongside five of my closest riding buddies, we hoped to cruise some of the highest elevation scree runs in the world amongst massive peaks. Though, what came as a greater surprise was just how much emotional weight each day of riding held. For the duration of our time south of the equator, we did whatever it took to burn the singletrack of Bolivia into our brains, even if it did end with a five-night hospital stay for some at the conclusion of the trip.

The group consisted of a Bellingham contingent—Leif Trott, Hannah Bergemann, Quinn Campbell, Matt Russell, myself—and Knight Ide from Vermont, who had been a boss to a few of us and would become a good friend to all. Once assembled, we met our guide, Yannick Wende, and set off on our journey.

Words by Myles Trainer

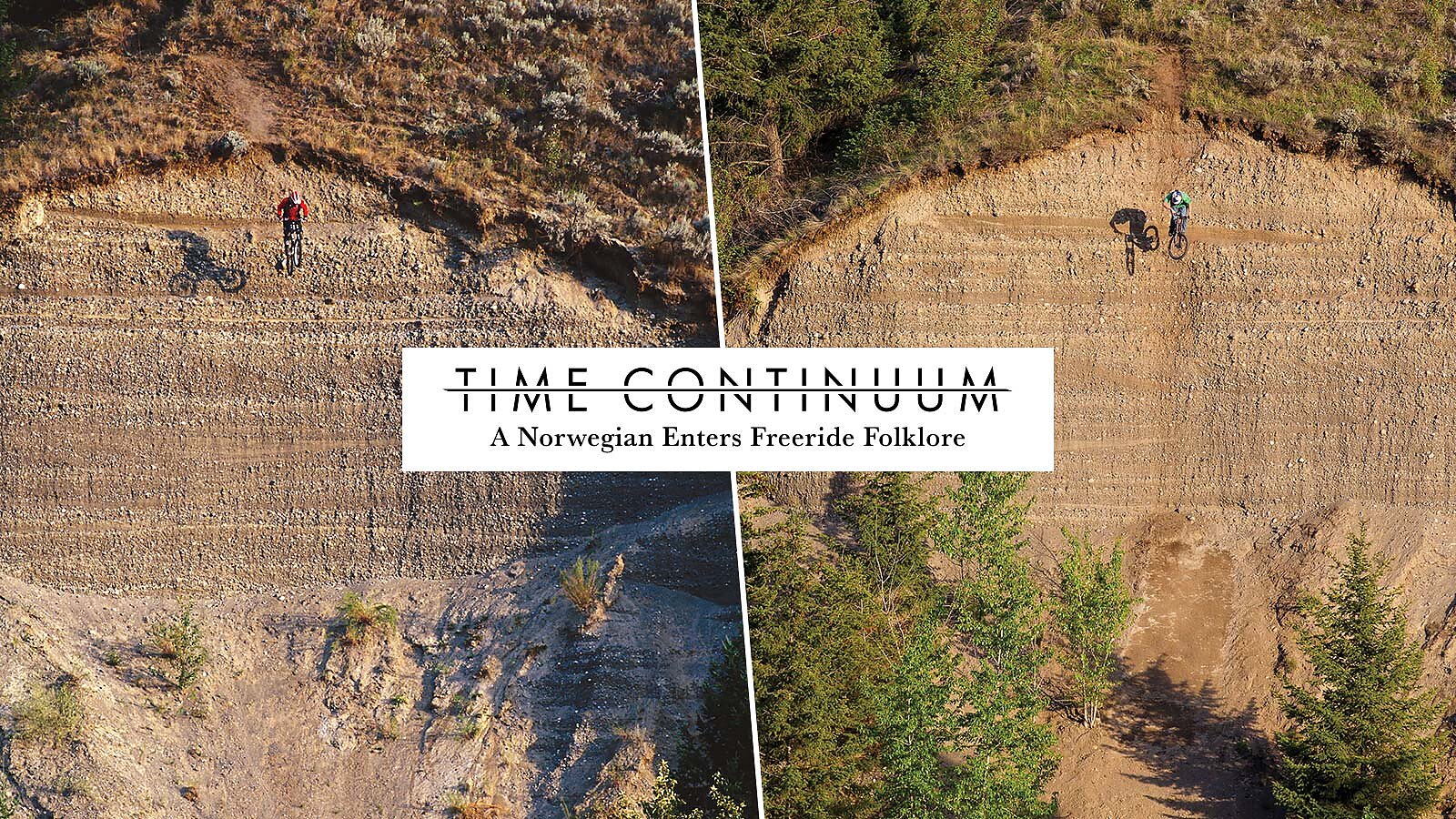

When listing the top 10 brain-melting moments in the history of freeride mountain biking on your fingers, Josh Bender’s four jumps off the infamous Jah Drop cliff near Kamloops, British Columbia, should be counted first, with both middle fingers, before raising each hand to the sky.

Bender hit the 55-foot drop once in 2000 and three times in 2001 but could never ride it out. Between 2000 and 2009, Freeride Entertainment released 10 movies in its “New World Disorder” (NWD) series. Josh Bender’s repeated, determined attempts at the Jah Drop in NWD 1 and 2 shook the cycling world to its core. It was huge. It was scary. We couldn’t look away.

Since then, the Jah Drop has become to mountain biking what the 100-foot wave is to surfing. Bender’s four shots at the Jah Drop and his style of riding ushered in a new era for mountain biking that saw the rise of Red Bull Rampage and other big mountain freeride contests. Still, the Jah Drop stands alone. And dormant.

Words and Photos by John Gibson